Days off, working from home or any form of sparing of young girls during their menstrual period is often a taboo topic in the Western Balkans even though it is a part of the reproductive healthcare of young people. Since it is a natural occurrence, girls are expected to ignore the nausea, dizziness, headaches, stomach aches and be maximally productive at work or college. Considering the fact that they can't reschedule exams and take sick leave every month, young women ignore symptoms that can be a signal of serious health issues.

"It was 7 AM. After a sleepless night due to pain, nausea and vomiting, I went to an exam, driven by the thought that if I missed it, I would have a much lower grade. No one would understand. The medication had apparently stopped working when I was on the public transport. The pain became almost unbearable and I got the urge to vomit again. I barely made it to college. I hoped that I would feel better if I went to the bathroom and washed my face. But that didn't help either. I did the test as soon as possible, with minimal concentration. I just wanted to get out of there and go home," says journalist Tamara Radovanović (27) from Niš, who had a surgery of a benign ovarian tumor two years ago.

She often ignored health issues during her period, thinking that those were normal menstrual problems, with which many women function smoothly.

"I can be an example of a person who neglected reproductive health for a while. I stopped going to the gynecologist because I thought that every menstrual problem was normal. It was a big mistake, because regular check-ups at least once a year are highly recommended. The growth on the ovary wouldn't become that big if I had gone to the gynecologist regularly. Maybe it could have been removed in a different way and not by classical surgery," she said.

However, she sees the pain as a friend who signalized to her that something was wrong. For this reason, Radovanović warns young women not to view pain as the cause of a problem that needs to be removed or ignored.

As teenagers, many girls learn to ignore pain and heavy periods. Research by the Biomed Center, which was mentioned by the World Health Organization on Menstrual Hygiene Day, showed that many adolescent girls in low- and middle-income countries are not well informed about menstruation. It seems they feel ashamed to find out some facts about their period. This lack of knowledge about menstrual health can affect self-confidence and personal development.

Therefore, it should not be surprising that many women in Serbia, when they feel pain during their period, take medicine and go to university or work, pretending that nothing is happening. The struggle for understanding and paid leave, expectedly, becomes the last thing girls talk about.

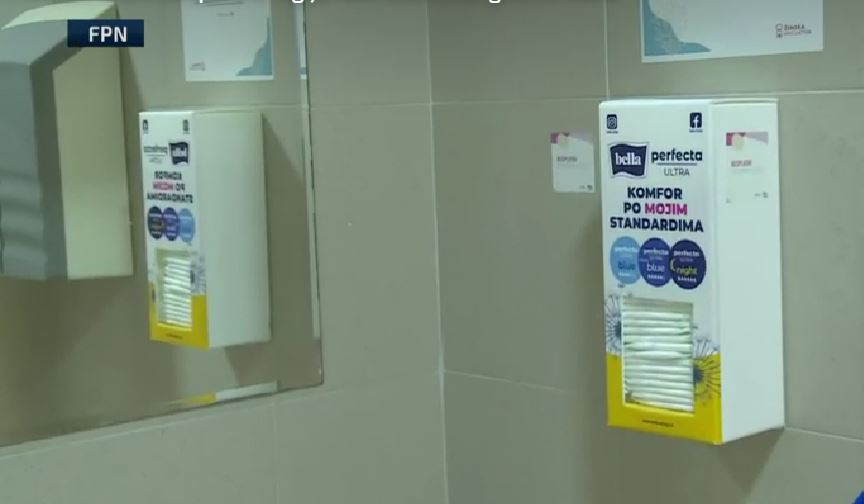

A good example of what can be achieved when awareness of the problem is raised is the action in which the Women's Initiative, in cooperation with seven faculties in Serbia, provided free sanitary napkins for female students. That initiative made a contribution to destigmatization of this topic in Serbian society.

If they want to be understood, women need to raise their voices themselves and realize that they don't have to go to work at all costs, says Tamara.

"In my newsroom, the collective is predominantly female and we understand each other when it comes to menstrual periods. Tolerance exists and there is no hesitation. If we gave ourselves more space, we would certainly encounter more understanding. However, legal solutions are indispensable," she adds.

From better laws to greater support for women during the menstrual cycle

At the end of last year, Spain adopted the Law on Reproductive Rights, which allows women with painful periods to take three to five free days per month. All women who experience dizziness, nausea, severe cramps and headaches during their menstrual cycle can take a paid absence from work with a medical certificate.

The Spanish Minister of Equality, Irene Montero, tweeted that the day this law was adopted was historic for the advancement of feminist rights, because women no longer have to go to work when they feel pain.

Master of social policy Marija Radovanović, who researched the position of women in the field of work and until recently collaborated with the Ministry of Human and Minority Rights and Social dialog of Serbia, says that such steps forward are also needed in Serbian legislation.

Improvements in laws in the field of labor, health care, gender equality, prohibition of discrimination and others could, as she says, need to be made so that women could be understood and supported during their period. These improvements could imply flexible work arrangements. This way, women would be able to work from home or have less working hours during their period.

"The Serbian work system could show understanding towards women by adjusting the work environment, which would imply that women can temporarily change their work tasks during their period", she points out.

However, she adds that the Serbian legislation could go a step further, and like women in Spain, women in Serbia could have paid menstrual leave.

The key to sparing is understanding. In order to achieve that, Radovanović says that it is necessary to introduce compulsory education about menstrual health. This would involve education about menstrual health in schools, the work environment and the community.

As she adds, it is important to make menstrual products available for all women through subventions, tax exemptions or initiatives that would provide free menstrual products in public places.

However, in order to achieve all of the above, menstrual hygiene needs to stop being seen as a taboo topic. According to Radovanović, anti-stigma campaigns are necessary for that.

'It is important to pass laws that support campaigns and initiatives for raising public awareness about menstrual health. This way, the stigma associated with menstruation would be reduced', she adds.

Radovanović points out that such measures would show concern for the physical and mental health of women, their economic and social position, and the overall quality of life.

As Marija Radovanović says, such improvements in legislation are often the result of social initiatives and activism.

"Creating and implementing the necessary measures requires analysis and research, consideration in the context of human rights, consideration of cultural, social and economic aspects, as well as open dialogue and cooperation between the government, employers, trade unions and civil society," she points out.

However, such measures could also cause negative effects, i.e. lead to greater discrimination of women during the employment process, during work and promotion.

Radovanović adds that the gap between men and women could be deepened because men would feel discriminated against. Applying such measures, in her opinion, could cause more sexism in the work environment. We need to be aware of these risks in order to prevent them.

"The basis for preventing such reactions would be education, informing employers, workers and society in general about menstrual health. It is also important to talk about the importance of these measures for the entire community," she adds.

The possibility of preventing discrimination was rejected in Italy, which is why a similar law was not adopted in 2017. Laws that enable menstrual leave and sparing the women during their period have also been passed in Japan, Taiwan, Indonesia, South Korea and Zambia. However, according to the Institute of Comparative Law, they are not always consistently implemented.

For the Western Balkans, such measures still seem far away.

Women in the region avoid talking about menstrual problems

Ajla Husanović (23), a student at the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering in Bihać, says that women in Bosnia and Herzegovina cannot take days off, but in several state companies they can ask for shorter working hours and less physical work.

However, as Husanović says, women in Bosnia and Herzegovina are ashamed to talk about menstrual problems and they rarely dare to ask their mates for undertanding during their period.

'It is still a taboo topic for a large number of women, so they avoid talking about it. They don't dare to ask for free days during their period. On the other hand, the male part of the population is not well informed about menstruation, which automatically leads to misunderstanding," she added.

Although Ajla herself has not encountered misunderstanding, she knows many girls who were in numerous unpleasant situations. It is surprising, she says, that the misunderstanding came firstly from other women.

Although girls in Bosnia and Herzegovina often avoid talking about it, she points out that menstrual absence would be a significant relief for them.

"Not all women have the opportunity to work from home. Some of them actually do heavy physical work. On the other hand, the jobs that are not based on physical work require effort and concentration. It is impossible to concentrate when the pain is severe. I believe that girls would be more satisfied, rested and more productive at work or college if they were allowed to have free days during their period," she adds.

Ajla claims that free days or less working hours during the menstrual cycle would mean a lot to her too, because she has painful and problematic periods.

Free days or less working hours during the menstrual period would also be significant for Albanian women, but they don't dare to talk about it, says journalist from Elbassan Dallandyshe Xhaferri (24). She points out that women in Albania can request leave when they experience severe pain, but without identifying the real cause - menstruation. Unlike Ajla, Dallandyshe believes that misunderstanding comes primarily from older men.

"Mentioning the menstrual cycle in the workplace is taboo in most cases, especially in public administration or factories. In most cases, men, especially older ones, do not understand women when it comes to their period. They can't comprehend the pain or mood disorder during these particular days. However, the situation is different with younger men. For example, in my workplace, we have overcome those barriers because we talk with each other about everything", she adds.

Dallandyshe says there have been cases when she took a day off because of menstrual pain and came back the next day when she felt better. She had no problem talking about that with her colleagues. However, during the school days, the situation was different.

"On the final exam in high school, I had terrible menstrual pain in the lower abdomen and immediately started sweating. It was the first time I felt such pain. A friend sitting behind me gave me a bottle of water, and the teachers gave me medicine. I felt better after everyone helped, but at that time, five years ago, I was more timid, shy and I didn't tell anyone why I felt that way," she recalls.

Dallandyshe adds that her reaction was not strange at all, considering the fact that in elementary schools in Albania, discussion over menstrual health is often being avoided.

"When we asked the biology teacher what the menstrual cycle was, he refused to answer, saying: 'Read about it at home.' However, already in secondary schools, these taboos are slowly breaking down, but not so much that women would ask for days off", she points out.

Although free days would mean a lot to young women, Dallandyshe is afraid that such measures can reduce the chances of women's advancement in a world that is already ruled by men, especially when it comes to getting a job.

However, more important than the possibility of discrimination in Spain was the alarming fact that about a third of women suffer from severe pain known as dysmenorrhea. At least that's what the research of Association of Gynecology and Obstetrics of Spain says. Apart from abdominal pain, symptoms of dysmenorrhea include acute diarrhea, headache, and fever.

Depressive episodes and loss of consciousness are frequent among girls during the PMS

Gynecologist Merima Atanasković says that she notices these symptoms, as well as premenstrual complaints such as irritability, depressive episodes, headaches, vomiting and loss of consciousness, in an increasing number of young women. That's why she warns girls not to ignore irregular and painful periods for the sake of work.

"Irregular and painful cycles, accompanied by heavy bleeding, and even scanty ones that last for two days are a signal that you should contact your gynecologist to find out what is the cause, and to find an adequate solution," she explains.

However, Atanasković says that after talking with her colleagues and patients, she concluded that the legal provision of paid leave is organizationally and economically unsustainable, especially in companies where women are predominantly employees. However, this does not apply to working from home or more free hours, for which the girls of the Western Balkans could also fight.

The key thing is the initiative and joint struggle to destigmatize the discussion about young women during the menstrual cycle. "Be bold", "Live by your rules", "There is no obstacle for you", slogans that are repeated over and over on commercials for menstrual products, should not motivate girls just to buy sanitary pads but also to fight for their rights in the field of work, health and education.

Author: Aleksandra Ničić (Faculty of Political Sciences – University of Belgrade)

Mentor: Assistant professor Marko Nedeljković, Department of Journalism and Communication Studies, Faculty of Political Sciences - University of Belgrade